A generation of outdoorsmen will forever recognize his weathered face peering through wire rimmed glasses, often under the shade of a well worn cowboy hat. It was an image seen by millions in the pages of Outdoor Life magazine, as he introduced boys of all ages to the beauty and adventures of the outdoors. His stories of places from Alaska to Zambia were anxiously read for their lessons in hunting and for an always gifted sense of storytelling. Jack O’Connor gave his readers a guide’s view of far off places that they could only dream of someday seeing with their own eyes.

John Woolf O’Connor was born in 1902, in Nogales, Arizona Territory. He was born in the West, when it still had more than a good bit of “wild” roaming the countryside. O’Connor grew up in a time when Bill Cody, Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, and Geronimo were still alive and roaming free. O’Connor’s parents divorced when he was five and his mother, a teacher, moved her family to Tempe where they initially lived in a large tent on a city block owned by her father.

Jack O'Connor was fixture on the pages of Outdoor Life for almost 40 years.

Jack maternal grandfather, James Wiley Woolf, was a pioneer westerner of standing in the community as well as a sportsman who appreciated firearms and enjoyed shooting. Jack’s paternal uncle, Jim O’Connor, also owned a ranch in the nearby desert country. Both men served as surrogate father figures for young Jack, teaching him to shoot and encouraging his interest in firearms and hunting. This was the early spark that led to a lifetime of adventures.

During World War I, Jack lied about his age and joined the Army at age 15, but was soon discharged when he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. He returned to school, graduating in 1919, and spent the summer shooting deer to feed an uncle’s sawmill workers in Sinaloa, Mexico. Later on that year, O’Connor joined the Navy and served aboard an old coal-burning destroyer and the battleship U.S.S. Arkansas. The Navy provided the needed perspective on life and he emerged from the service with a desire to get an education. “I saw how hopeless the lives of my uneducated shipmates were,” O’Conner said.

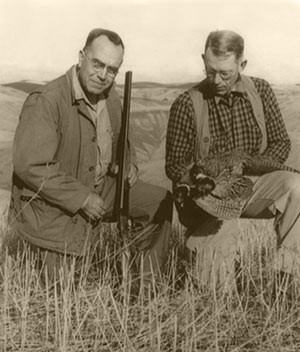

O'Connor (right) in pursuit of pheasant near his home in Idaho.

O’Connor attended college at Tempe Normal (now Arizona State University ) for two years, then University of Arizona for a year, before graduating from University of Arkansas in 1925. He then enrolled in graduate school at University of Missouri where he met his future wife, Eleanor Bradford Barry, and earned his masters degree in English/Journalism in 1927. He then married Eleanor and accepted a teaching position at what is now Sul Ross University at Alpine, Texas.

In the tiny Texas town of Alpine, Jack taught Eleanor to hunt, and explored the Big Bend country of Texas and northern Chihuaha, Mexico. In 1931, he returned to Arizona as a public relations staff member at the State Teachers College at Flagstaff (now Northern Arizona University ). While in Flagstaff, Jack published his first works in Sports Afield and Field and Stream magazines. It was done as something to supplement his depression era salary, but it quickly became his life’s work. His first published article was a conservation piece entitled “Arizona’s Antelope Problem,” and was published in Outdoor Life in 1934.

O'Connor allowed his readers to tag along on all his hunts via the pages of Outdoor Life.

In 1945, O’Connor resigned from university life and began his full time career as an outdoor writer with Outdoor Life. It was in the pages of Outdoor Life that the world of the outdoors came alive for children of the post war era. O’Connor combined colorful stories of the pursuit of trophy animals, with expert advice on guns, gun care, marksmanship, and stewardship of the outdoors. He was the preeminent voice of a generation of outdoor writers.

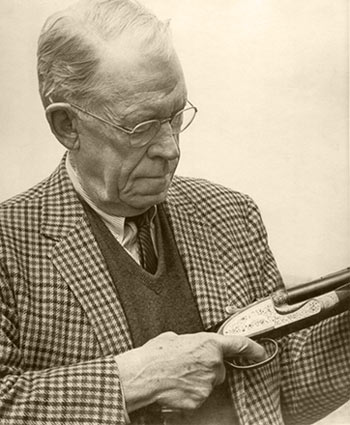

Perhaps O’Connor’s most lasting professional contribution was as the shooting editor for Outdoor Life. He brought his expansive knowledge of guns to readers and offered insight earned over years in the field. He was also extremely influential and almost single-handedly popularized the .270 as the rifle to own for a generation of hunters. It still remains the most popular rifle among American hunters today.

O'Connor examines one of his prized side by sides.

Although, O’Connor is most remembered for his works in Outdoor Life, he also published fourteen books that still garner wide critical acclaim for their expertise. The Rifle Book is considered standard reading for any lover of firearms. His other notable works included: The Complete Book of Rifles and Shotguns, The Big Game of North America, The Art of Hunting Big Game in North America, and The Best of Jack O’Connor.

Eventually, O’Connor made his permanent home on the Snake River in Idaho, but he was often away, hunting exotic animals in the far off corners of the earth. From the 1940s through the early 1970s, O’Connor stalked his prey on four continents (North America, Europe, Africa, and Asia), and in such places as Rhodesia, Kenya, Tanzania, Tanganyika, India, Iran, Scotland, Spain, Italy, Mexico, the Yukon, Alberta, British Columbia, Alaska, and most of the Western United States. Sheep hunting was his passion and he was only the fifth man to achieve two “grand slams” of all four varieties of North American sheep — Desert Big Horn, Rocky Mountain Big Horn, Dall, and Stone. At one time, O’Connor held the No. 10 in Stone and No. 12 in Dall trophies in the world records. In 1972, he was selected as the Winchester’s “Outdoorsman of the Year.”

O’Connor died of a heart attack on January 20, 1978, aboard the S.S. Mariposa as it was returning to San Francisco from a three-week cruise to Hawaii.

He was beautifully remembered, in a style that is warmly reminiscent of O’Connor’s, by Jim Rikhoff in a 1979 issue of The American Rifleman.

Very few men are legends in their own lifetimes, which is probably a good thing when one considers the possible consequences of too many egos abroad at one time. A lot of people think they are legends, but very few are bonafide “living legends” and even fewer are nice about it.

I knew Jack for some twenty years. We hunted hunted quite a number of states and a couple of Canadian Provinces. We also hunted Mexico, Scotland, Spain, and Italy–sometimes even with a little success. We always planned to take an African safari together, but somehow the years passed and we never did.

Jack and I were hunting sheep together in the Cassiar Range of British Columbia and the Pellys of the Yukon when he was in his early seventies. We both took a stone sheep in the Cassiars, but Jack never fired his rifle in the Yukon on what was to be our last hunt together, which I think now we both knew.

We were with a brand new outfit, Teslin Outfitters, who had just taken over a country that had not been hunted in six years. They also had not had a chance to do much more than put in an excellent base camp at Francis Lake, so when we took off from there with our pack string we were really striking off into new territory. It was just as if we were old mountain men around the next bend, through the next stream, and over that last ridge. Jack was exhilirated. After a day or two on the trail, as we made camp at dusk, he told me that of all the places he had hunted–he guessed that he loved the high country of the Northwest the best.

We pressed on for five days and saw no game. Finally even the last rudimentary man made trails petered out and we followed increasingly narrow and steep game paths. There were so many blowdowns and so much buck brush that we had to get down off our horses and cut our way through. It soon became obvious that Jack, partially crippled from an automobile accident years before and circulatory problems from plain old age, could not make it any farther in that country.

He insisted that we make a camp by a stream in the open country and I go ahead with one guide while he remained with the rest. I went off and a couple of days later took a sheep. We returned and Jack was overjoyed. We had made the trip a success–for myself obviously, but also for Teslin’s first hunt and lastly for him on what he knew might be his life trip to his beloved high country. We packed up and headed back and once almost got another sheep for Jack. He didn’t care about not getting the shot, but seemed strangely content to be once more on horseback, with friends, in another country, with a river to cross and maybe some trees to rest under…..I have no doubt that he has found those trees.

In 2006, after years of work by Jack O’Connor enthusiasts and with full support from the state of Idaho, the Jack O’Connor Hunting Heritage and Education Center opened its doors. Located at Hell’s Canyon Visitor Center within a couple of miles of where Jack lived on the Snake River, the Center houses his trophies, guns, a display of his books and other mementos, and Outdoor Life works. For more information, click here.

Pingback: FIELD | Using Choke to Improve Accuracy for the Fall Bird Season « F.M. ALLEN Camp Smoke

As a collector of Mort Kunstler paintings, it’s interesting to read about the writers associated with the art. Keep up the good work with the interesting articles.